The transition to the Bronze Age was a period of significant upheaval for many communities, as the established social structures of the preceding Copper Age began to crumble. Understanding this pivotal era—what triggered these changes and how people adapted—remains a challenge for archaeologists. A recent study offers a new perspective through the examination of Murayghat, an ancient site in Jordan, providing a glimpse into how societies responded to major disruptions.

Background: The Copper Age and its Disruption

The Copper Age (or Chalcolithic) saw the rise of settled farming communities across the Levant region of the Middle East. This period was characterized by advancements like copper mining and smelting, but around 5,500 years ago, many of these settlements experienced decline—either shrinking in size or being entirely abandoned.

Climate Change and Societal Collapse

Previous research suggests a combination of factors likely contributed to this societal shift, including climate change and social disruption. The Chalcolithic period was notably humid, supporting vegetation that would not typically grow in the region today. This period of increased rainfall culminated in a transition towards a drier climate, which may have significantly impacted agricultural practices and community stability.

Murayghat: A Different Kind of Settlement

Murayghat, located near the city of Madaba in Jordan, stands apart from the typical residential communities of the earlier Chalcolithic period. According to archaeologist Susanne Kerner from the University of Copenhagen and lead author of the study, it appears to have been primarily used for ceremonial gatherings rather than daily living.

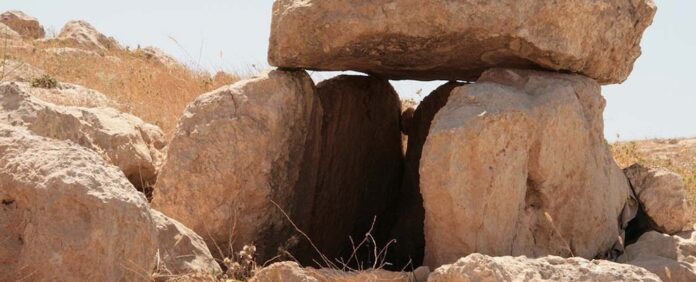

“Instead of the large, settled communities with smaller shrines common in the Chalcolithic, our excavations at Early Bronze Age Murayghat reveal clusters of dolmens, standing stones, and large megalithic structures indicating ritual gatherings and communal burials, rather than living quarters,” Kerner explains.

Dolmens: Markers of Ritual Activity

Dolmens, also known as portal tombs, are monumental burial structures typically composed of two upright stones supporting a horizontal capstone. Kerner and her colleagues meticulously documented the remains of over 95 dolmens at Murayghat, providing detailed descriptions of more than 20 of them, all dating back to the Early Bronze Age.

While none of the dolmens contained human remains, their resemblance to better-preserved dolmen fields in the region strongly suggests a ceremonial purpose.

Beyond the Dolmens: Central Hilltop Features

The site’s prominent hilltop also features stone enclosures and carved bedrock, further supporting the interpretation of a space dedicated to ceremonial use. Notably, there’s little evidence of typical domestic amenities such as hearths, which would normally be found in residential areas.

Diverse Architecture and the Movement of People

The variety of architectural styles at Murayghat is unusual for a residential site. Kerner suggests this diversity could be explained by different groups of people traveling to the site and bringing their own unique traditions.

“The layout of the site and the prominence of the dolmens back this idea, as do many of the artifacts uncovered there,” she points out. These artifacts include large communal bowls and other items commonly associated with rituals and feasting.

Adapting to a Changing World

While the drying climate significantly reshaped the sociopolitical landscape of the late Chalcolithic Levant, it didn’t force all communities to disappear. Some areas indeed experienced steep declines or even abandonment, but others found ways to persist.

“People had to find new ways to manage a situation where traditional values and behaviors no longer worked,” Kerner writes. “New methods of organizing life—and death—had to be developed, within a society dealing with a major disruption to everyday life and characterized by weak social hierarchies.”

Unanswered Questions and the Importance of Murayghat

Understanding how these adaptations occurred remains challenging. After thousands of years, fully reconstructing the events at Murayghat in the Early Bronze Age may be impossible. However, the preservation of so many clues at the site makes it a uniquely valuable resource for archaeologists.

“Murayghat provides us with fascinating new insights into how early societies coped with disruption by building monuments, redefining social roles, and creating new forms of community,” Kerner concludes. The site offers a compelling glimpse into the resilience and adaptability of ancient communities facing profound societal and environmental change.