Breakthroughs in computing power and neuroscience are converging, enabling researchers to simulate human brain activity at an unprecedented scale. For the first time, supercomputers now possess the computational capacity to model billions of neurons – a complexity comparable to real biological brains. This development isn’t just about processing speed; it’s about the emerging ability to test fundamental theories of brain function that were previously impossible.

The Rise of Exascale Computing

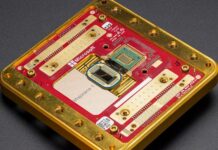

The key driver is the advent of “exascale” computing, where systems can perform a quintillion calculations per second. Only four such machines currently exist worldwide, with one of them – JUPITER, based in Germany – being utilized by researchers led by Markus Diesmann at the Jülich Research Centre. The team has successfully configured a spiking neural network model to run on JUPITER’s thousands of GPUs, simulating a network equivalent to the human cerebral cortex: 20 billion neurons connected by 100 trillion synapses.

This leap in scale is critical. Smaller brain simulations, like those of fruit flies, lack features that emerge only in larger systems. Recent advancements in large language models (LLMs) demonstrate this principle: bigger networks exhibit qualitatively different behaviors. As Diesmann explains, “We know now that large networks can do qualitatively different things than small ones. It’s clear the large networks are different. ”

From Theory to Testing

The simulations are grounded in empirical data from human brain experiments, ensuring anatomical accuracy regarding neuron density and activity levels. This allows researchers to test core hypotheses about how the brain works, such as the mechanisms of memory formation. For example, they can expose the simulated network to images and observe how memory traces develop at different scales.

Beyond basic neuroscience, these simulations offer a novel platform for drug testing. Researchers can model neurological conditions like epilepsy and evaluate the impact of various pharmaceuticals without human subjects. The increased computational speed also allows for studying slow processes like learning in real-time, with greater biological detail than ever before.

Limitations and Future Outlook

Despite these advancements, simulating a brain isn’t the same as replicating one. Current models lack critical elements found in real brains, such as sensory input from the environment. As Thomas Nowotny of the University of Sussex points out, “We can’t actually build brains. Even if we can make simulations of the size of a brain, we can’t make simulations of the brain. ”

Furthermore, even fruit fly simulations fall short of fully mirroring real animal behavior. The field is still limited by our incomplete understanding of brain function.

Nevertheless, the ability to run full-scale simulations marks a pivotal moment in neuroscience. It offers unprecedented opportunities to test hypotheses, refine theories, and accelerate drug discovery, ultimately bridging the gap between biological complexity and computational modeling.