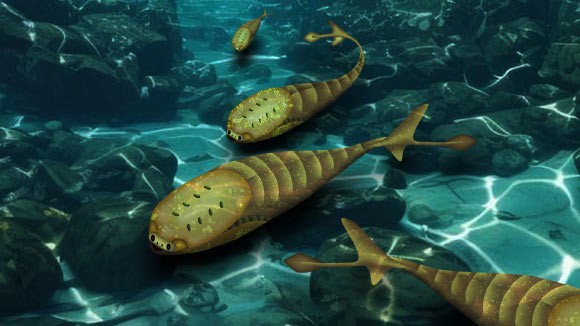

A major puzzle in the history of vertebrate life – why fish lineages seemingly appear abruptly in the fossil record long after their origins – has been linked to the Late Ordovician mass extinction (LOME), a catastrophic event approximately 445–443 million years ago. New analysis reveals that this extinction wasn’t just a period of loss, but a fundamental restructuring of early marine ecosystems that paved the way for the rise of jawed and jawless fishes.

The Mystery of the Missing Fossils

For decades, paleontologists have noted a curious gap: vertebrate lineages seem to appear relatively suddenly in the mid-Paleozoic, despite their origins stretching back to the Cambrian period. The usual explanations involve incomplete fossil records or “ghost lineages” (species that existed but left no trace). However, research led by Wahei Hagiwara and Lauren Sallan at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology suggests a more dramatic cause: LOME effectively reset the playing field for vertebrate evolution.

How the Extinction Reshaped Marine Life

The Late Ordovician extinction was a two-stage event characterized by rapid climate shifts, fluctuating ocean chemistry, glaciation, and sea level changes. These conditions decimated marine life, including widespread losses among early jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes) and primitive jawless fish like conodonts. This devastation created a prolonged period of low biodiversity known as Talimaa’s Gap, lasting for millions of years.

The key finding is that surviving species didn’t simply rebound evenly across the globe. Instead, they diversified in isolated “refugia” – pockets where conditions allowed them to persist. This localized evolution led to unique lineages that would eventually repopulate the oceans.

The Rise of Jaws in Isolation

The earliest definitive evidence of jawed vertebrates appears in South China, one of these key refugia. These early sharks and their relatives remained geographically restricted for millions of years, evolving in isolation before spreading to other ecosystems. This pattern mirrors recovery from other mass extinctions, like the end-Devonian event, where biodiversity takes decades to recover.

The study confirms that the post-extinction period wasn’t about rapid expansion, but gradual diversification in isolated pockets. This explains why modern marine life traces its origins back to these survivors rather than earlier, now-extinct groups like conodonts.

“By integrating location, morphology, ecology, and biodiversity, we can finally see how early vertebrate ecosystems rebuilt themselves after major environmental disruptions,” says Professor Sallan.

The researchers compiled a new, comprehensive database of Paleozoic vertebrate fossils to reconstruct these ancient ecosystems, quantifying the dramatic increase in gnathostome diversity following LOME. The evidence suggests that the extinction wasn’t just a setback for early fish – it was a catalyst for the evolutionary innovations that would define them.

In conclusion, the Late Ordovician mass extinction didn’t simply wipe out life; it reshaped its trajectory, creating the conditions for the emergence of jawed vertebrates and ultimately influencing the course of fish evolution. This research provides a new framework for understanding how major evolutionary events can be driven not just by survival, but by the unique pressures of ecological restructuring.