Researchers at Northwestern University have achieved a significant milestone in the pursuit of treating spinal cord injuries: successful regeneration of damaged human spinal cord tissue in a laboratory setting. This breakthrough, detailed in recent findings, builds upon prior success in animal models, bringing the prospect of human therapies closer to reality.

The Challenge of Spinal Cord Injuries

Spinal cord injuries often result in permanent paralysis because the central nervous system struggles to repair itself. Damaged nerve cells, or axons, don’t easily regenerate, and the body’s natural response—the formation of a glial scar—further blocks regrowth. This scar tissue acts as a physical barrier, preventing severed nerve fibers from reconnecting. The core problem isn’t just the initial damage; it’s the body’s reaction to it.

The ‘Dancing Molecule’ Therapy

The research team, led by biomedical engineer Samuel Stupp, previously demonstrated success in reversing paralysis in mice using a material called IKVAV-PA. This material contains supramolecular therapeutic peptides —molecules designed to mimic the natural movement of receptors on nerve cells. These “dancing molecules” more effectively interact with cells, prompting axon regrowth.

The key insight here is that biological processes aren’t static. Nerve cells and their receptors are constantly in motion, so a therapy needs to match that dynamism to be effective. Static molecules may never encounter their targets, whereas rapidly moving ones can engage cells more frequently.

From Mice to Human Tissue: Organoids as a Bridge

While animal models are crucial, they aren’t perfect substitutes for human biology. To validate their approach, the team turned to spinal cord organoids – tiny, lab-grown models of human spinal tissue. These organoids, derived from adult stem cells, developed many of the structural characteristics of a real spinal cord over several months.

Researchers then induced injuries—both cuts and compression trauma—in the organoids, mirroring the types of damage seen in real-life spinal cord injuries. The organoids responded as expected: nerve cell death, glial scar formation, and inflammation. This confirmed that the lab-grown tissue accurately replicated the biological response to injury.

Dramatic Regeneration in the Lab

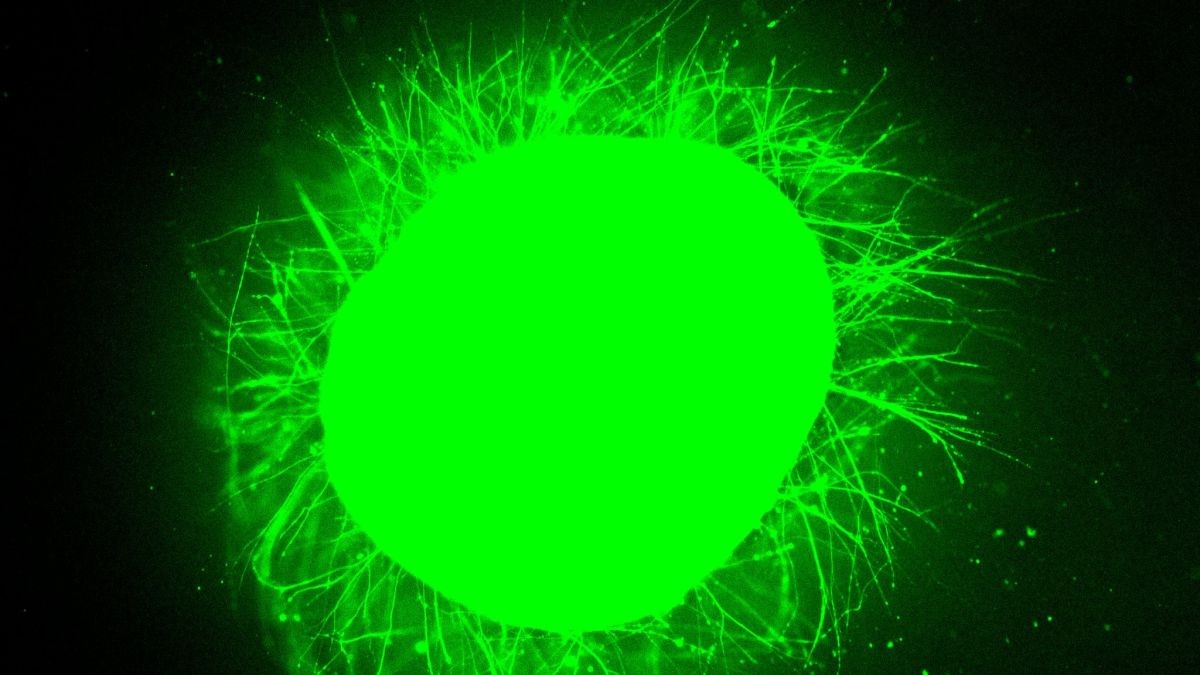

After injury, some organoids were treated with IKVAV-PA, while others served as controls. The results were striking. The treated organoids showed significantly reduced inflammation and scarring, alongside substantial nerve cell regrowth. The liquid therapy gelled into a scaffold, actively encouraging axon regeneration.

The difference was visually clear: the glial scar in treated organoids was barely detectable, unlike the dense, impenetrable scars in the control group. The team also observed a reduction in chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans, molecules associated with inflammation and injury response.

What This Means for the Future

This research offers a crucial validation step for a potential human therapy. While clinical trials are still years away, the consistent success across both animal and human tissue models is highly encouraging. The ability to test therapies in lab-grown human tissue provides a critical bridge between animal studies and human trials, reducing the risk of unforeseen complications and accelerating the development of effective treatments.

This work highlights the power of biomimicry – designing therapies that work with the body’s natural processes rather than against them. If further studies confirm these results, the prospect of restoring movement to paralyzed individuals may become increasingly realistic.