Traditional Hawaiian fishponds, known as loko iʻa, are proving to be remarkably effective in protecting fish populations from the escalating impacts of climate change. A recent study from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) reveals that these ancient aquaculture systems offer a natural buffer against rising water temperatures, bolstering food security in a rapidly warming world.

How Loko Iʻa Maintain Stability

The research, published in npj Ocean Sustainability, demonstrates that fish within loko iʻa experience significantly less temperature fluctuation than those in surrounding open-water environments. This stability is primarily due to freshwater input into the ponds, which regulates both surface and subsurface temperatures. Rising ocean temperatures pose a major threat to fish populations globally, but loko iʻa offer a proven solution.

The Science Behind Resilience

Lead author Annie Innes-Gold, a recent Ph.D. graduate from UH, explains: “We found that while rising water temperatures lead to declines in fish populations in open estuaries, loko iʻa fish populations remained more resilient. This is likely due to the temperature regulation provided by freshwater input.” The study highlights the critical role of freshwater sources in maintaining stable aquatic ecosystems.

Combining Tradition and Modern Management

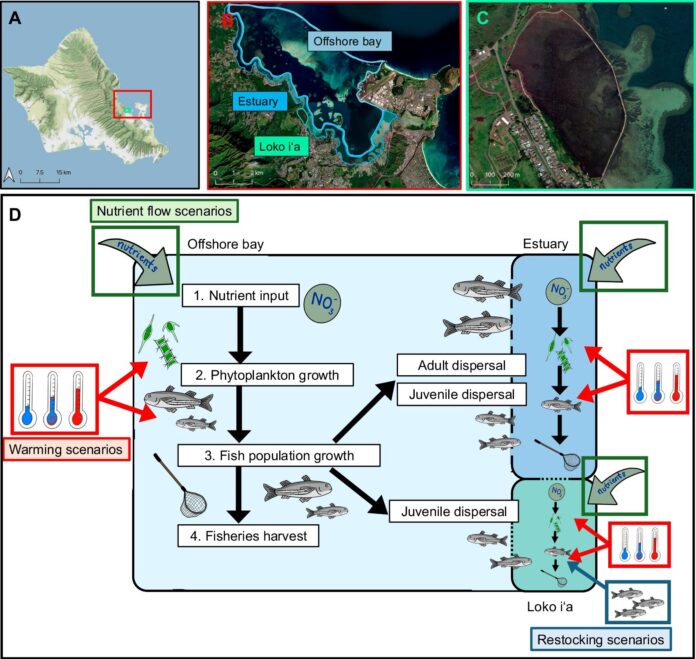

The effectiveness of loko iʻa isn’t solely due to temperature regulation. The study also shows that combining fisheries regulations, nutrient flow restoration, and fish restocking further enhances resilience. These combined efforts offset the negative impacts of warming and substantially increase both short- and long-term fish densities within the ponds.

Indigenous Knowledge Guiding Modern Science

This research underscores the value of integrating Indigenous knowledge with modern scientific practices. The team, comprised of university researchers, resource managers, and loko iʻa practitioners, demonstrates the power of collaborative approaches.

“These findings highlight how important freshwater inputs are as a source of temperature regulation,” Innes-Gold states. “They also support the importance of biocultural restoration in terms of enhancing fish populations and increasing social–ecological resilience in a changing climate.”

The success of loko iʻa provides a model for climate-resilient aquaculture. By combining traditional ecological knowledge with modern management techniques, Hawaiʻi is demonstrating a pathway toward sustainable food security in a warming world. The preservation and restoration of these ancient systems offer a powerful tool for mitigating the impacts of climate change and ensuring the long-term health of marine ecosystems