Researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz, have demonstrated that small clusters of lab-grown brain tissue can be trained to solve an engineering problem – balancing a virtual pole – using carefully designed electrical feedback. This proof-of-concept experiment shows that neural tissue in a dish can adaptively learn, which could provide new insights into neurological diseases and the brain’s capacity for plasticity.

The Experiment: Teaching Brain Organoids to Balance a Pole

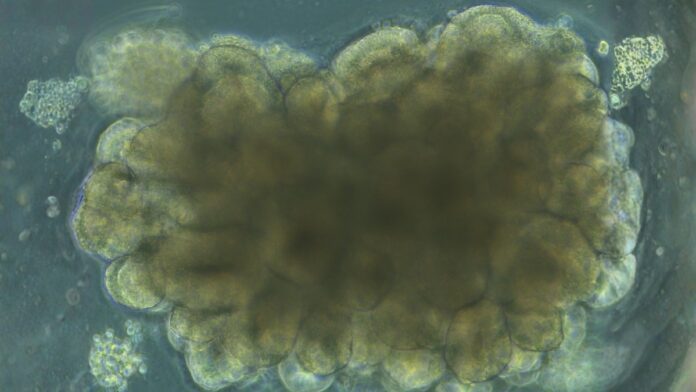

The experiment used cortical organoids, small, three-dimensional structures grown from mouse stem cells that mimic certain aspects of brain tissue. These organoids aren’t capable of thought or consciousness, but they can send and receive electrical signals, and their connections can be modified through stimulation. The task was to control a “cartpole” – a simulation where a virtual cart moves left or right to keep a hinged pole balanced vertically.

This problem is notoriously difficult for artificial intelligence systems because it requires constant, fine-tuned adjustments, not just a single correct response. The organoids were connected to the virtual environment, and their electrical activity was interpreted as commands to move the cart. The key was adaptive feedback : when the organoid performed poorly, it received a brief burst of electrical stimulation. An algorithm adjusted which neurons received this stimulation based on whether similar patterns had previously led to better control.

Why This Matters: Understanding Brain Plasticity and Disease

This isn’t about creating functional biocomputers. Instead, it’s about understanding how neurons adapt to solve problems. According to Ash Robbins, a researcher at UC Santa Cruz, “We’re trying to understand the fundamentals of how neurons can be adaptively tuned to solve problems. If we can figure out what drives that in a dish, it gives us new ways to study how neurological disease can affect the brain’s ability to learn.”

The results were significant. Organoids given adaptive feedback balanced the pole in 46% of cycles, compared to 2.3% for those given no feedback and 4.4% for those given random stimulation. This shows that the tissue’s neuronal connections can be tuned through structured feedback.

The Limits and Ethical Considerations

The organoid’s learning is short-lived. After just 45 minutes of inactivity, it reverts to baseline performance. Future research will focus on improving its memory, possibly by increasing complexity. David Haussler, a bioinformatician involved in the study, emphasized that the goal is to advance brain research and treat neurological diseases, not to replace robotic controllers with lab-grown tissue.

The use of human brain organoids would raise serious ethical concerns, but for now, this research offers a unique window into the fundamental mechanisms of brain plasticity.

This study demonstrates that living neural circuits can be adaptively tuned through structured feedback, a finding that could revolutionize our understanding of how the brain learns and adapts, and how neurological diseases disrupt these processes.