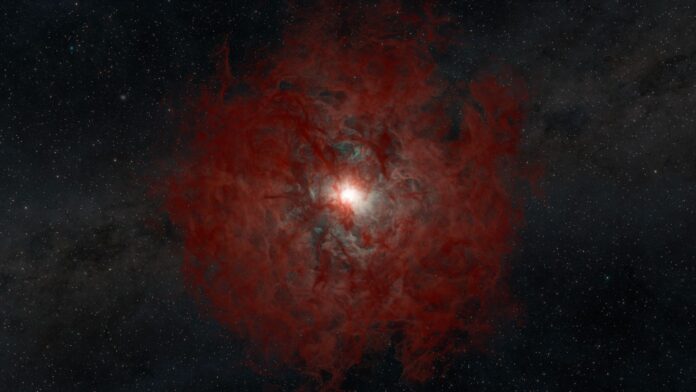

Astronomers have observed what appears to be the silent formation of a black hole within the Andromeda Galaxy, marking one of the clearest confirmations yet that stars can collapse into these gravitational wells without the dramatic supernova explosions traditionally expected. The discovery, based on analysis of NASA’s NEOWISE mission data, challenges previous assumptions about black hole formation and suggests they may be far more common than previously believed.

A Star’s Sudden Disappearance

The star, designated M31-2014-DS1, was located approximately 2.5 million light-years from Earth. It originally shone at roughly 100,000 times the brightness of our Sun, comparable to the well-known red supergiant Betelgeuse in Orion. Over a decade, starting around 2014, the star steadily dimmed before effectively vanishing by 2023—reducing to just one ten-thousandth of its original brightness. The team, led by Columbia University astronomer Kishalay De, initially noticed the anomaly while reviewing archival NEOWISE data.

“Stars that are this bright, this massive, do not just randomly disappear into darkness,” De said, recalling the moment when follow-up observations at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii revealed no trace of the star. Subsequent verification with the Hubble Space Telescope confirmed the disappearance.

Challenging Established Theory

For years, the dominant theory held that black holes form only from the collapse of extremely massive stars, culminating in a spectacular supernova. However, M31-2014-DS1 weighed just 13 times the mass of our Sun—relatively small by typical black hole-forming standards. This raises the possibility that stars of moderate size may quietly collapse under their own gravity, forming black holes without the violent expulsion of matter.

The implications are significant: if a star of this size can become a black hole without a supernova, then the universe likely contains many more black holes than previously estimated. This changes our understanding of stellar evolution and the population of black holes in galaxies.

What Remains Behind?

The collapse appears to have occurred rapidly, possibly within hours. What remains is not the star itself, but a faint infrared glow from dust and gas spiraling around the newly formed black hole. This material is orbiting too quickly to fall directly in, forming a rotating disk that will slowly feed the black hole over time—similar to water swirling down a drain.

Future Observations

Over the coming decades, this infrared signature is expected to fade as the remaining debris spirals inward. The relatively close proximity of the Andromeda Galaxy means this process will remain visible to powerful observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Though directly imaging the black hole itself is currently beyond our technological capabilities, astronomers anticipate that as the surrounding gas clears, high-energy X-rays may eventually emerge, providing further confirmation.

This discovery provides a new method for identifying similar events: rather than monitoring billions of stars for sudden disappearances, astronomers can now search for brief infrared flare-ups—possible indicators of an impending quiet collapse.

The vanishing star in Andromeda offers a unique glimpse into stellar death, suggesting that black holes may form in more subtle ways than previously thought and are far more prevalent in the universe than we once imagined.